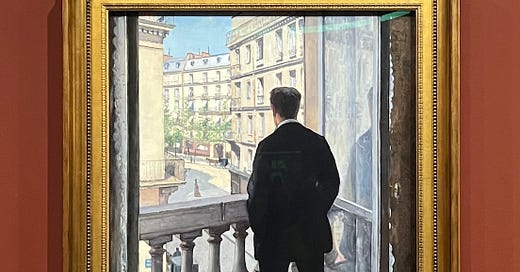

‘Caillebotte: Peindre les Hommes’ ended it’s run recently at the Musée d’Orsay. It is intended to celebrate the 130th anniversary of Gustave Caillebotte’s death as well as a few recent acquisitions of his work at internationally notable institutions. The exhibition visits the two institutions, Musée d’Orsay (Boating Party) and the J. Paul Getty Museum (Young Man at His Window), as well as the Art Institute of Chicago which has loaned Caillebotte’s most recognized work, Paris Street, Rainy Weather for the duration of the tour.

This exhibition sparked a bit of controversy from those who argued the focus on his work with the male figure is not a full depiction of his career as an artist. There were valid points raised about the texts of the exhibition insinuating Caillebotte’s sexuality was an impetus for this subject matter. Personally, I take umbrage with the criticism. While the textual insinuations do harken to an old-fashioned way of history writing, I find the focus on his male figures both interesting and important. Perhaps my opinion is biased (who’s isn’t?) due to my graduate research into the male nude, but “Painting Men” was, for me, a curational success.

It must be said, one matter which impacted my enjoyment of the show was the crowd. The musée provided free access to the exhibition for museum ticket holders as well as reserved entry slots which you could pay for. Thankfully, the reserved entry was sold out on the day we wanted to go because I would have been angry to have paid and entered in the exact manner and order as the rest of the public. There was no policing the number of viewers at all. It was loud, and hot, and stuffy and I found myself actually feeling a bit sick towards the end. If I had perhaps arrived earlier in the day or did not have my propensity for nausea, this show could have been one of my favorites of last year. Nevertheless, I did thoroughly enjoy it.

Caillebotte is unique among his peers for his male subjects, but he is not unique in that he painted what was available to him. While others at the time were painting gardens and their families, Caillebotte did the same, but his family consisted of his brothers and his gardens were Haussmannian Paris and sailing practice. Whether Caillebotte was homosexual or not, we can appreciate his male subjects as a welcome anomaly in this age.

In a time when the genders were strict in their separation and confinement, Caillebotte’s work evaluates the duality of man and manhood. Along with classic, expected portraits of bourgeois men, his work highlights the virility of young working men juxtaposed with pieces showing the more feminine, domestic lives of the men he knew. There are men playing cards, lounging around their houses and famously, exiting the bath. Caillebotte opened the door (or the window, if you pardon the joke) to the emerging idea of social realism for a new class. Without evaluating the morality of their status, Caillebotte painted bourgeois men who had time to relax and sail and didn’t rely on painting as a form of income, but of enjoyment.

Caillebotte’s style is reminiscent of his contemporaries, and the respect he had for other artists is clear in both his work and the accompanying exhibition of his personal collection which he bequeathed to the state. We see the influence of Courbet’s everyday workers and Degas’ graceful dancers in works like Floor Scrapers. The suavity of the floor scrapers’ bare backs coupled with hypnotic movement of the curled shaving and sharp diagonal lines mix with the soft lighting to present a depiction of men at work unlike any before.

I would be remiss, as a scholar of the nude, if I didn’t mention Caillebotte’s. In a room of their own in the exhibition we find three of his nudes. Caillebotte did not often paint nudes in fact but here we have one woman and two men, one of which (Man at His Bath) is quite well known in the modern era, all things considered. Caillebotte’s nudes subverted the standard for the time, presenting the bodies without academic pretext, exactly as they were, and even more shockingly, by reversing the gendered expectations. Whether or not Caillebotte intended to make a statement, painting these two men in the intimacy of their bathrooms, in positions of vulnerability and normalcy as they dried themselves casts us as voyeurs of these men and redefined the conventions of the time.

‘Caillebotte: Painting Men’ travels to the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, from February 25 – May 25, and then the Art Institute of Chicago from June 29 – October 5.

Very interesting

I enjoyed the controversy raised in this piece. It was an eye opener about an artist I had never heard of but this piece has pushed me to want to research more. Thank you!